#2 – The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

Director: John Huston

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Walter Huston, Tom Holt, Alfonso Bedoya, Bruce Bennett

Cert: PG

Running time: 118mins

Year: 1948

Accolades:

1949 Academy Awards

Best Director

Best Screenplay (Adapted)

Best Supporting Actor

AFI 100 Years… 100 Movies (2007)

Ranked #38

AFI 100 Years… 100 Movie Quotes (2005)

No. 36 – “Badges? We ain’t got no badges! We don’t need no badges! I don’t have to show you any stinking badges!”

Contemporary review:

Treasure of Sierra Madre (Warner) is one of the best things Hollywood has done since it learned to talk – Time, 1948

Electric Shadows rating: ![]()

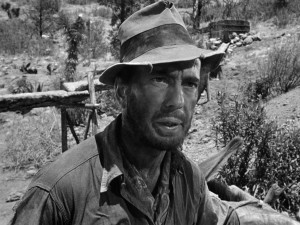

The lowdown: John Huston’s 1948 masterpiece of avarice and moral corruption is a riveting psychological thriller wrapped in the garb of a sweaty, noir-ish Western. Humphrey Bogart delivers his finest performance as Fred C. Dobbs, a down-and-out down Mexico way consumed by greed when he and his companions strike gold on the slopes of the titular mountain. Huston’s father Walter won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance as an excitable prospector who knows a thing or two about the human condition. Huston, Jr. deservedly picked up golden statues for his taut script, based on B. Traven’s anti-capitalist source novel, and direction that moves plot pieces with the precision of a grandmaster. In typical baffling Oscar fashion, despite these awards Best Film that year went to Olivier’s Hamlet.

The full verdict: Even before his name was Indiana Jones, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg knew what Indy would look like. He’d resemble Bogart in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

On the eve of Raiders of the Lost Ark’s principal photography, Spielberg showed the film to cinematographer Douglas Slocombe for a sense of what the young director envisioned.

Raider’s South American prologue plays like a potted version of The Treasure…; three men battling harsh terrain for fortune and glory, doomed by greed and betrayal is the core of Huston’s movie.

But watching the film now, it’s surprising the impression it left on the Raiders wunderkinds.

Bogart’s Dobbs is some distance from Ford’s resourceful Jones. Panhandling in 1920s Tampico, Mexico, Dobbs is duped by a slimy conman and is none too handy in a fight, requiring the assistance of fellow drifter Curtin (Holt) to right wrongs.

And when the two hit the prospecting trail, along with Klondike Gold Rush pro Howard (Walter Huston), Dobbs is the one faltering early, demonstrating ignorance of the land when mistaking pyrite for gold and is also the first to succumb to violent paranoia.

Huston signposts the inevitable collapse into distrust early on, with Huston, Sr. delivering the film’s key line:

“As long as there’s no find, the noble brotherhood will last. But, when the piles of gold begin to grow… that’s when the trouble starts.”

Director Huston takes grim delight in illustrating this, Dobbs falling from grace in spectacular style. Wide-eyed and optimistic at the beginning, his doom is foreshadowed by the flickers of light burning in his eyes whenever the precious metal is mentioned.

His destructive arc, vividly brought to life by Bogart’s twitchy, burning performance, bests even his work on In A Lonely Place, and never once recalls the tough smarts of Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe. It should have won him his Oscar a full three years before The African Queen sailed by.

The character’s pain partly derived from the city-slicking Bogart being less than thrilled at the shoot on location in Mexico; the first time a studio picture had shot the bulk of a movie away from the backlot.

It’s easy, however, to see what attracted adventurer John Huston to the project years earlier, before a stint making military documentaries earned him the Legion of Merit and put this on hold.

Flawed men, an exotic backdrop rich in recent tumultuous history (both the bandits and tough government Federales of the time provide unforgettable background flavour), and the opportunity to test himself in a hostile environment must have been irresistible to Huston, now seasoned with first-hand experience of man’s cynicism following WW2.

Visually, Huston resists the charms south of the border, shooting the landscape either in bleached out high key lighting or with shadowy, noir style gloom.

And save for scenes depicting approaching bandits or Federales, Huston pays no lip service to the epic vistas, opting instead for claustrophobic framing that grows tighter on characters’ faces the higher distrust rises (a trick repeated by Sidney Lumet in 12 Angry Men).

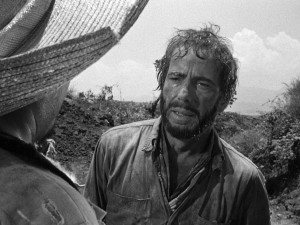

Huston also manifests Bogart’s demons in the unforgettable shape of Alfonso Bedoya’s bandit chief, Gold Hat, speaker of the film’s most famous, and misquoted “Badges” line.

Gold Hat’s posse are on hand for two briskly paced shoot-outs, Huston understanding he has to throw at least a little gunplay the audience’s way, and the bandit’s final stand-off with Dobbs is a moment of breathtaking casual brutality.

But, Huston is master of here: unwaveringly convinced of his methods (even as studio boss Jack Warner fumed over the escalating budget and endless shooting schedule), his steady hand ensures the film stays the right side of melodrama throughout vicious twists, cowardly acts and a climactic divine wind that shows everyone just who’s boss.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’s legacy lives on, in such films as Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan and most notably Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. A fascinating companion piece, it retains the avarice and corruption but ups the lead character’s IQ as he moves from gold digging to oil drilling.

As an ironic epilogue, Huston released movie gold into the world, but did not see a fortune in returns. Too bleak and with an A-lister audiences this time could not root for, it took time for the film’s status to grow.

But, as the movie testifies, there’s more to life than money.

Rob Daniel

[youtube id=”IIDlYsedmXo”]