The BFI Player Japan 2020 season continues in June with a collection dedicated to Yasujiro Ozu, joining fantastic collections on Akira Kurosawa and Classic Japanese movies.

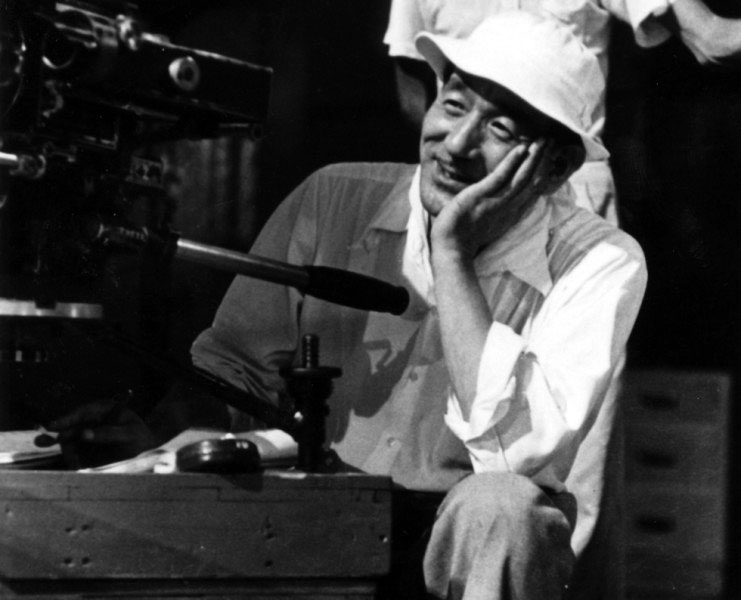

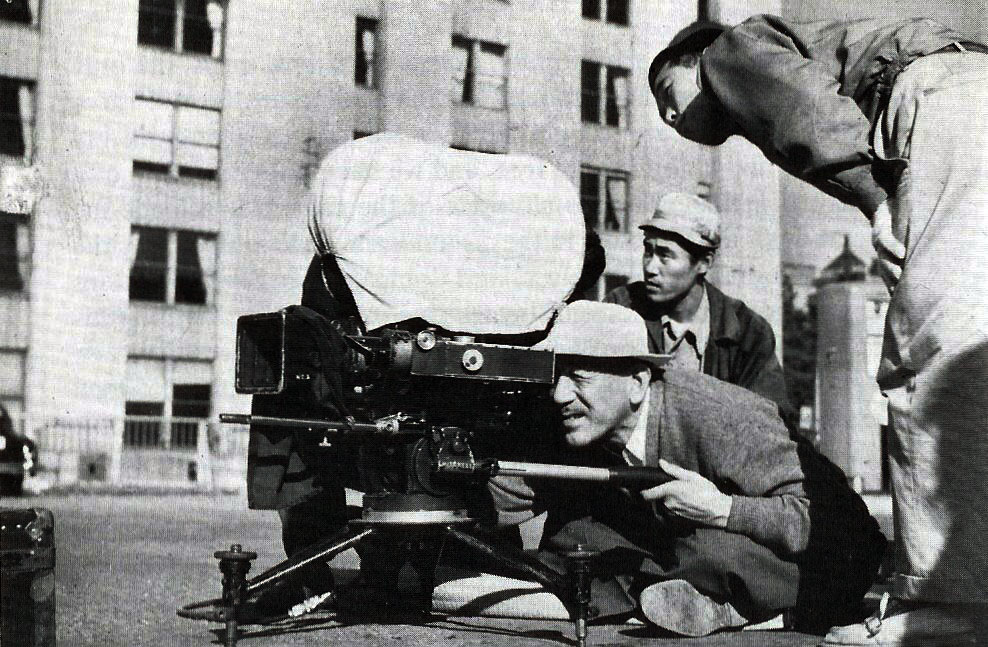

A giant of Japanese cinema, Ozu made 54 films before succumbing to cancer on his 60th birthday in 1963. The BFI Player collection will feature 25 of the 36 surviving Ozu movies, by far the most that have been made available on VOD.

The collection includes the numerous masterworks Ozu made, including Early Spring, his final movie An Autumn Afternoon and his most famous film, Tokyo Story. The latter has appeared in the top 10 of Sight and Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time polls since 1992. In 2012 it placed no.3 behind Vertigo and Citizen Kane, and also topped the magazine’s Top 10 list selected by directors.

You should watch it, it’s really special…

The collection will also feature some of the rarer titles, including films from the 1930s. Ozu is best remembered for his quiet studies of family life, but these 30s titles often saw the director in the thriller and comedy genre.

But while Ozu is one of Japan’s greatest directors, most audiences may not have watched even his most famous movies, making this collection a highlight of the 2020 movie calendar.We had the opportunity to talk with Dr. Alexander Jacoby about Yasujiro Ozu and why he is so important to Japanese cinema. An expert on Japan and Japanese film, Alex explains why the director’s films will dazzle new audiences.

For more information on BFI Japan 2020, click here

To view Japan 2020 on BFI Player, click here

Alex, many thanks for talking to us today. Could you tell us a little about yourself?

Alexander Jacoby: Sure, I’m Alex Jacoby, senior lecturer in Japanese Studies at Oxford Brookes University, with a particular focus on Japanese cinema. I came to an academic career through Japanese cinema, discovering the films when I was a teenage undergraduate. They led me to Japan to discover the culture that produced them.

For the last decade I’ve been teaching students to, I hope, love Japanese films too! I’m also the author of A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors and a forthcoming book on Hirokazu Kore-eda, which the British Film Institute will publish in collaboration with Bloomsbury.

I’m working with the BFI on the Japan 2020 programme, and have worked on past programmes including retrospectives of Kozaburo Yoshimura and Kaneto Shindo, Akira Kurosawa, plus a Tomu Uchida season which I co-curated with Jasper Sharp.

What is it about Japanese cinema that originally attracted you and continues to do so?

In 1998 when I was 19, the BFI hosted a major Kenji Mizoguchi retrospective. The leaflet that came through the door read, “The comparisons are as inevitable as they are unfashionable: Mizoguchi is the cinema’s Shakespeare, its Bach and Beethoven, its Rembrandt, Titian and Picasso.”

To which I thought, my gosh, I just have to see these movies. So I commuted down to London every evening throughout that February to follow the retrospective.

I saw a director who had this extraordinary distinctive style; long takes, long shots, all very graceful and elegant. He seemed to be saying a lot about Japan, but also a lot about the human condition.

I didn’t know much about Japan or the human condition then, so those films really brought me in. That retrospective was a sell-out, so the BFI followed it later in the year with a slightly less comprehensive Ozu retrospective. So then I saw all these films by Ozu, who has a diametrically opposed style: he keeps his camera very still, his films are very quiet.

Here were two opposite directors, yet both so sublime. I wanted to discover the culture that produced the films. I lived in Japan after graduating, and was eventually encouraged to do a PhD on Japanese film. That led to me making it my career.

Today we’ll be discussing Yasujiro Ozu, who is the subject of a collection in the BFI Player’s Japan 2020 season. How would you describe his movies to the uninitiated and why is he an important director to showcase?

AJ: Summing it up in a single sentence, Ozu shows you the tiny, quiet details of everyday life, and through that he shows you the whole world.

His films are largely in the ‘home-drama’ genre. They are about the choices we make, about parents and children, how we relate to the people we love, and the generation gap. Anyone who has been part of a family should be able to identify with Ozu’s films and characters.

Alongside this, if you watch Ozu you learn about the particular experience of Japan at a particular time. One reason he makes films about the generation gap is because that gap was pretty damn huge at a time when Japan was transforming so rapidly: transforming politically, socially, in terms of technology, in terms of lifestyle.

The country moved from being a military tyranny in the 1930s, when Ozu was in the early part of his career, to becoming a liberal democracy in the 1950s and 60s. So, with that as a background it’s no surprise that the way a parent lives, thinks and feels is totally different to how their son or daughter does.

This is a theme we see in The Only Son, which is Ozu’s first sound film and began his mature style. We also see it in Late Spring, Early Summer, Tokyo Story and An Autumn Afternoon.

And because we are living in a world which, if anything, is changing even more rapidly, I think these films are still incredibly relevant and modern.

Yes, it might surprise audiences how accessible these films are.

AJ: I think that’s right. Ozu is often talked about in a clichéd way as being the most Japanese of Japanese directors. In a sense, yes, he charted the experience of Japanese people living through a tumultuous period. But, beyond that he deals with universal issues about people who are very close to each other, but who see things in a very different way.

It could be that people think Ozu is more alien than he is simply because his style is so particular and distinctive.

On that point, Ozu was famed for the style he developed over his career. Could you tell us a little about it and how it makes his films so special?

AJ: The thing you always read about Ozu is that he never moves the camera. That’s not entirely true, but it does become truer as his career goes on. Watching the postwar films, you’ll see he moves his camera very rarely; he tends to find a composition he likes and lets the action play out within it. If he wants to change position, he’ll cut.

Yet, it’s not a style that keeps you at a distance from the characters. There are often medium close-ups in his films because he wants you to see subtle shifts in facial expression.

But, it is fair to say his films consist of long scenes of people talking in rooms, punctuated by what is called a pillow shot. This is when you cutaway to something inanimate: famously a vase in Late Spring, or laundry flapping in the wind.

So it’s a very quiet style, allowing you time to reflect. But, because of that quietness you can be brought to see how something as small as a subtle smile passing over a face makes all the difference to the moment and how someone feels.

Or you see that laundry flapping in the wind, white and bright after being washed, and think, okay, characters are now starting anew.

Some people have said this is a style that comes out of Zen Buddhism. Ozu is buried in a Zen temple and on his grave he has the Zen character 無 (mu), meaning “nothingness”.

Other people have disputed that. Apparently, when Ozu himself was asked about the connection, he said, it’s all these foreigners who don’t really understand my films and say they’re all about Zen!

What’s certainly true is that he liked Zen temples and gardens. One of the famous scenes in Late Spring is filmed at Ryoanji, a celebrated stone garden in Kyoto. His films do share the placid beauty of those classically Japanese spaces.

When I was watching the films, those pillow shot cutaways felt fresh and modern.

AJ: Well, interestingly one of the big debates around Ozu centred on the question of was he a modernist? The famous critic David Bordwell talked about him being an avant-garde filmmaker. But in some ways Ozu is very much a genre filmmaker, the ‘home-drama” being a recognised popular Japanese genre.

Ozu didn’t invent the Japanese home-drama. His namesake Yasujiro Shimazu was making domestic dramas in the 1920s. When the BFI Southbank is able to open again we are planning to show the 1934 Shimazu film, Our Neighbour Miss Yae. Anyone who loves Ozu should love that film as well.

But, I think you can say Ozu perfected the genre and gave it a precision, delicacy and elegance unmatched by his contemporaries.

I suppose if you think of it in film studies terms, Ozu is very much an auteur director in that he kept working in the same vein over and over again. So in that sense he fits into the category of directors likely to be celebrated. But, it’s also a very Japanese thing: Japanese classical artists might paint subtle variations on the same mountain landscapes.

Ozu makes films about families who aren’t exactly the same but are very similar. The subtle shifts between films encapsulate the great differences between different people, different places and different generations.

Ozu was also quite self-deprecating about this singular focus, comparing himself to a tofu maker. He said he can make fried tofu, boiled tofu and so on, but was not suddenly going to start making other dishes.

AJ: That’s right. Another comparison that has been made by Donald Richie, the great pioneering critic of Japanese cinema, and also Tom Milne in Sight and Sound, is with Jane Austen. Austen said she only had a little bit of ivory a few inches wide, and that was all she knew. But, at the same time, that microscopic focus allows an artist to explore something in great detail.

The big difference between Ozu and Austen is that Austen lived in a very sheltered milieu, whereas Ozu lived in a traumatic milieu. He experienced the growth of militarism in Japan, he lived through the war, which he hated.

He was conscripted in the late 1930s, sent to China, and seems to have had a traumatic time. He never spoke about his war experiences, although ultimately he landed a kind of cushy option when he was sent to Singapore to watch captured Allied films. After the war ends, he lives through this period of the American Occupation. Then onto Japan finding its way as an independent country when the Occupation ends in 1952, while going through a process of dramatic modernisation and industrialisation.

I wrote Jane Austen in my notes as so many Ozu films feature a wedding as a plot point. But, I’ve not seen a film of his where the wedding is actually shown; they are only discussed before and after the event. Also, weddings don’t seem to be joyous occasions in Ozu films – in An Autumn Afternoon a character compares one to a funeral!

AJ: I think that’s true, and in a sense it’s because Ozu doesn’t seem to believe in rapture. For him, a wedding is just moving to the next stage of life. A lot of Japanese people in the early and mid-20th century would have had, not exactly an arranged marriage, but something like an arranged marriage. Parents would set up a meeting with an eligible chap for their daughter. Then the daughter would have to say what she thought of him.

So there wasn’t the idea in Japan as in Western culture that you usually marry for love. Also, there was a strong social pressure to marry.

An interesting aspect of Late Spring is that it was produced in 1949, when there’s a new liberal constitution that has been devised partly under the sponsorship of the occupying Americans.

One of the things it guarantees is the freedom to choose a spouse. I think Late Spring is asking the question, so what does that mean? You may be free to choose to marry who you want, but what if you don’t want to marry? Do you have the freedom not to choose a spouse?

So Late Spring is very much a film questioning how free you are when something is guaranteed legally, but there are strong social pressures, plus emotional pressures people internalise.

We’re talking about films that dramatise the pressure to marry, but it’s worth mentioning Ozu himself chose not to get married. He lived with his mother until she died, which she did only a year before him.

Similarly, his great star Setsuko Hara, who played different characters each called Noriko in Late Spring, Early Summer and Tokyo Story, and appeared in other Ozu films, she too chose not to marry.

So there’s an interesting contrast between films depicting characters who feel pressured to accept the social norm, and a director and a star who opted against that in real life.

You mentioned the cliché of Ozu being described as the most Japanese of Japanese directors, but he was also a fan of American films. Is this interest in Hollywood cinema evident in his work?

AJ: It’s evident in certain ways and at certain times. It’s there in his early films. His first, long lost film, 1927’s The Sword of Penitence, was actually a remake of a Hollywood movie.

In his earlier years he was experimenting with genres that might surprise us now. If you watch That Night’s Wife or Dragnet Girl, both of which are on the BFI Player, you see him making crime thrillers. Dragnet Girl is close to the gangster movies Hollywood was producing at that time in the early 1930s.

People who think Ozu might be too sedate for them may want to try those early crime films and see if they still think that!

The influence of silent era comedy is also visible. When the critic Tony Rayns reviewed I Was Born, But… for Time Out, he said something like the pace being worthy of Buster Keaton at his best. It’s true, there is a lively humour in some of those early comedies.

Even once you get into the later years and the point where you think his style has become much more removed from Hollywood’s influence, you can still see traces. 1953’s Tokyo Story was apparently partly inspired by Leo McCarey’s 1937 film Make Way for Tomorrow, which is again about an elderly couple whose children neglect them in their old age.

Of course, the films are completely different because they operate within the different conventions of Hollywood and the conventions of Japanese cinema. But, there still seems to be an interest in Hollywood cinema on Ozu’s part in his post-war career.

Can Ozu’s influence be felt in modern cinema, both inside Japan and elsewhere?

I think so. In a sense he has become an inescapable influence, something that was true in Japanese cinema since his death. The new wave director Shohei Imamura was Ozu’s apprentice and complained about the way he directed actors, saying Ozu put them in too rigid a mould.

But, once you get to Imamura’s later career and a film like Black Rain, which is about the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing, you find him framing shots in quite an Ozu-like manner. So, it seems to be an influence Imamura wanted to renounce but discovered eventually he couldn’t.

When the season plays at BFI Southbank we’re planning to show Muddy River, a film from the 1980s which is confessedly in the Ozu model. A home-drama, it is even made in black and white and has a similar understated style, mostly static camera and so forth.

Many Japanese directors who came to the fore in the 1990s were quite strongly influenced by Ozu one way or another. Tomoyuki Furumaya, for example, is a director making subtle, quiet films about everyday life.

Hirokazu Kore-eda is the most famous modern Japanese film director, and in interview says he feels more influenced by the filmmaker Mikio Naruse than Ozu.

But, on the other hand he uses exactly the same compositions of characters seated around a table, plus those cutaways to, for example, smoking chimneys or a vase of flowers, which seem to directly evoke specific images from Ozu’s films. Plus, like Ozu, Kore-eda’s subject is the Japanese family and its dissolution.

Outside Japan, I think the Taiwanese New Wave filmmakers who emerged in the 1980s were influenced by Ozu. Hou Hsiao-Hsien especially owes him a great debt, and even went to Japan to make a film called Café Lumiere, which seems a direct homage.

Outside Asia, directors such as Jim Jarmusch and Wim Wenders have expressed a debt to Ozu. In the last few years we have seen this arthouse thing called ‘slow cinema’ becoming a bit of a trademark. I think a lot of the practitioners of ‘slow cinema’ seem to feel that Ozu is in the background.

But, when you watch these modern arthouse films and then go back to Ozu, you might end up being shocked at how sprightly his films feel by comparison. And we have to remember that although he influenced many current arthouse directors, Ozu himself was not making arthouse movies. He made commercial films for a mass audience in Japan.

From the BFI Player’s Yasujiro Ozu collection, what three films would you recommend as a good introduction to the director?

AJ: Of the famous masterpieces from the post-war era, I’d say start with Late Spring. It’s undoubtedly one of Ozu’s great films, but it is slightly shorter than Early Summer or Tokyo Story. It’s also lighter in mood for long stretches, although it contains genuine pathos. But, there are bouncy, humorous scenes and the acting’s lively. You also get to see Kyoto looking fabulously beautiful in 1949, before it was modernised.

So, I think Late Spring has a lot of surface pleasures, but is archetypal Ozu: a great story about people in a difficult family situation learning how to move toward the future. In this, Ozu is our contemporary because we live in a time of great uncertainty and change, similar to the Noriko character in the film.

If you’re willing to take a chance on a silent movie, I would recommend I Was Born, But…, a film that is accessible, charming and fast paced. People not overly familiar with silent films will often say the acting is too exaggerated or that the films are overly melodramatic.

That certainly isn’t the case in early Japanese cinema. In this delightful film you have wonderful performances from the kids and the adults.

Speaking of silent films, you might want to check out Ozu’s early crime films on the BFI Player, like Dragnet Girl, to see him doing something other than stories about the family.

It’s worth going to the end of his career and his final film, An Autumn Afternoon. A kind of remake of Late Spring, it’s interesting to compare the two, but also to see how well Ozu handled the use of colour, with these deep red autumnal motifs.

Could you tell us a little bit about your part in BFI Japan 2020 and why it’s an important season?

AJ: I worked with the BFI on the development of the season, starting last summer and autumn. In particular I’ve been working with James Bell to curate the 20th century section of the programme.

When London’s BFI Southbank opens again we’re planning to show a whole range of classic Japanese films stretching from the 1920s to 1999. Some will be famous films from directors such as Kurosawa, Ozu and more recently Takeshi Kitano. But, some films will be new to most audiences in Britain.

Why is it important the BFI is dedicating a substantial amount of time and effort to celebrating Japanese cinema?

I’ll have to give the old-fashioned answer that Japanese cinema is one of the greatest in the world. Over the past century it has contributed a disproportionate percentage of masterpieces in a vast range of genres. It is diverse in tone, theme and style; Japanese films can be quiet and subtle or dramatic and extravagant.

These films are also a good entry point for people wanting to understand more about Japanese culture, while reminding us of our common humanity and the things we share.

To finish, what non-Ozu films from the BFI Player collections would you recommend?

AJ: On the BFI Player, we have a big Akira Kurosawa package. As he is the most famous Japanese director, many readers will know him already. But, they might want to take this opportunity to get more acquainted with his work. Some of my favourite Kurosawa movies are not actually the famous samurai films, but the thrillers with contemporary settings like Drunken Angel and Stray Dog.

I’m fond of Mikio Naruse, and several of his films are on the BFI Player. He’s a serious and compelling dramatist who really draws you in. Kwaidan by Masaki Kobayashi must be the most beautiful ghost story ever filmed.

People interested in issues surrounding gender, which are very contemporary in 2020, might want to look to Funeral Parade of Roses, which deals with the queer underground of Japan in the late 60s and anticipates some issues people are thinking about nowadays. (This is currently available on BFI Blu-ray and will arrive on BFI Player in August)

I tend to go for the more prestige pictures, but there are a lot of popular and cult films on the list. Seijun Suzuki’s gangster movie Tokyo Drifter and Lady Snowblood with Meiko Kaji are both accessible and genre based.

You also have modern independent directors like Naomi Kawase, who is one of the most important female filmmakers currently working, plus some Hirokazu Kore-eda.

Then you have films from directors like Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who really straddles genre and independent filmmaking. People say he’s a director of horror films, but he himself says he works in genre in order to better distance himself from it.

There really is a huge range of stuff on BFI Player.

Moving to a time when we can again show films at the BFI Southbank, we’ll be screening some real hard-to-see treasures.

One of the frustrations about loving Japanese cinema is that you can quite easily see Kurosawa and Ozu movies, but when it comes to great directors such as Heinosuke Gosho, Shiro Toyoda, Hiroshi Shimizu, or Kozaburo Yoshimura it is far more difficult. The opportunity to see their work is typically limited to the odd touring retrospective and, with one or two exceptions, you won’t find their films subtitled on DVD.

So I would recommend prioritising films from directors such as these when we all get back into the cinema.

One film scheduled for the BFI Southbank season that I should single out is Fallen Blossoms. This was made in 1938 by Tamizo Ishida, a director little known in the West or in Japan. The film is about a geisha house and features an all-female cast, with not a single man appearing onscreen. Now, that’s a rare enough achievement in 21st century cinema, let alone a film made 82 years ago during a particularly conservative period in Japanese history.

My personal favourite director is Kenji Mizoguchi. He’s not so fashionable these days, but is as great a director as Kurosawa and Ozu. Mizoguchi’s Sansho Dayu will be screening at the BFI and is one of the few films you could hand to someone and say, “If you watch this, it will teach you how to live!” It’s such a humanist masterpiece.

Fantastic, I’ll be sure to check it out when it’s screened. Which just leaves me to say many thanks Alex for taking the time to speak with us about Ozu and BFI Japan 2020.

AJ: Not at all, it has been great to discuss him and it. I hope people will be inspired to download Ozu’s movies and other riches of Japanese cinema on the BFI Player.

Many thanks to the BFI for arranging this interview and Dr. Alexander Jacoby for being so generous with his time

Rob Daniel

Twitter: rob_a_Daniel

iTunes Podcast: The Movie Robcast

LISTEN TO EXCERPTS OF THIS INTERVIEW ON THE MOVIE ROBCAST

Or if you subscribe to Spotify…

Pingback: Kristy Matheson on Kinuyo Tanaka: A Life in Film

Pingback: BFI Player's Japan 2020 Anime Collections showcases Hosoda Mamoru

Pingback: BFI Japan 2020's Classics Collection - 5 Must-See Movies

Pingback: Tokyo Story - Yasujiro Ozu's masterpiece astounds almost 70 years later

Pingback: Yasujiro Ozu and BFI Japan 2020 (feat. Alexander Jacoby) - The Movie Robcast