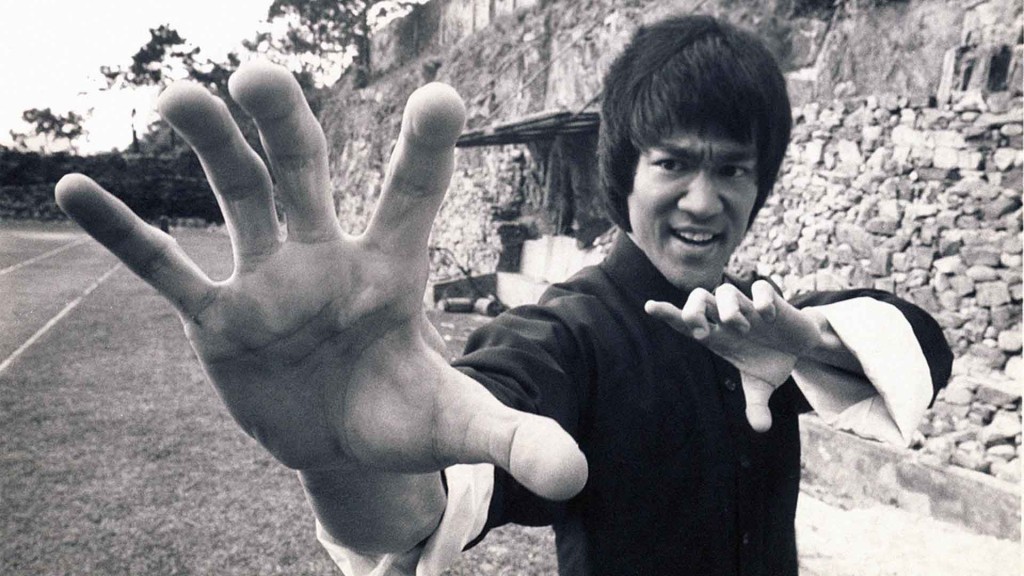

“When the opponent expands, I contract. When he contracts, I expand. And when there is opportunity, I do not hit. (Raising his fist) It hits all by itself.” – Bruce Lee, Enter the Dragon

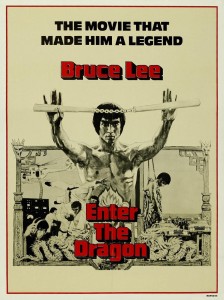

Enter the Dragon was released 40 years ago on July 26th 1973. Tragically, Bruce Lee had died six days previously, so never saw the phenomenon his martial arts classic would become over the next four decades.

Enter the Dragon was released 40 years ago on July 26th 1973. Tragically, Bruce Lee had died six days previously, so never saw the phenomenon his martial arts classic would become over the next four decades.

Originally intended as a cash-in on both James Bond and the imported Chinese action films that were doing big business at the time, what makes the movie so special?

The answer is Bruce Lee. Enter the Dragon was intended to be a global showcase for the Chinese-American actor, proving he could move from Eastern to Western action star.

In this respect it was a smash hit, making $25m at the US box office in 1973 and $90m worldwide, all from an outlay of $850,000. To date Enter the Dragon has made an estimated $200m for Warner Brothers, the only studio willing to greenlight the movie.

A former child star from a theatrical family, Lee was born Lee Chun Fan in San Francisco in 1940 – the year of the dragon. His Chinese name means “gaining fame overseas” and he would do this twice in his life.

First, when his family relocated to Hong Kong shortly after Lee’s birth, he became a child star in local movies. His stage name then, Siu Lung, meant “Little Dragon” – the persona already beginning to take shape.

First, when his family relocated to Hong Kong shortly after Lee’s birth, he became a child star in local movies. His stage name then, Siu Lung, meant “Little Dragon” – the persona already beginning to take shape.

Second was when he returned to Hong Kong in the late 1960s after a period back in the US. In America Lee had taught his own brand of kung-fu, Jeet Kun Do, a pick-n-mix approach to existing styles. Lee believed no single discipline was superior therefore the fighter must flow between different schools of combat.

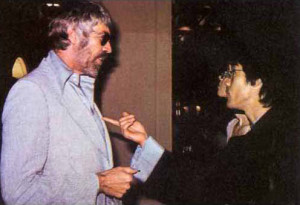

He counted Hollywood stars including James Coburn (above picture), Chuck Norris and Steve McQueen as friends but, other than the role of Kato in the short-lived Green Lantern series, his US screen career in this period amounted to little more than walk-ons.

Hong Kong studio Golden Harvest offered Lee a two picture deal. These two films, The Big Boss and Fist of Fury, made him a legend in the East, despite local surprise that the Little Dragon was now an action man.

Imagine Macaulay Culkin becoming Jason Statham and you’re close.

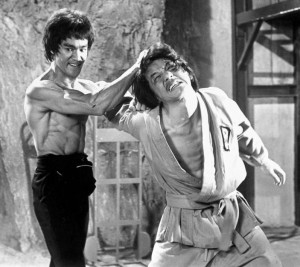

After Fist of Fury (right), Lee had enough power to form his own company, Concord Productions, through which he made his third movie, Way of the Dragon. Moving west for location shooting in Rome and employing karate champions Chuck Norris and Bob Wall, Lee was already eyeing an audience beyond the local Chinese market.

After Fist of Fury (right), Lee had enough power to form his own company, Concord Productions, through which he made his third movie, Way of the Dragon. Moving west for location shooting in Rome and employing karate champions Chuck Norris and Bob Wall, Lee was already eyeing an audience beyond the local Chinese market.

He would get that opportunity to expand his audience on his next film, Enter the Dragon.

Enter the Dragon’s unsung hero is producer Fred Weintraub (below with Lee), a former Warner Brothers executive who after seeing Lee’s Hong Kong movies knew something was about to explode.

Weintraub approached WB chairman Ted Ashley directly to secure half the required budget after every studio had turned him down, including Warner Brothers.

A mash-up of James Bond movies, Blaxploitation flicks and Hong Kong action films, Enter the Dragon had its sights firmly set on the paying movie going public.

A mash-up of James Bond movies, Blaxploitation flicks and Hong Kong action films, Enter the Dragon had its sights firmly set on the paying movie going public.

Michael Allin’s script, a loose remake of Dr No, sends Lee (playing a character conveniently named Lee) on a mission to infiltrate the island of rogue Shaolin monk Han (Shih Kien). Suspected of drug running and human trafficking, Han is also missing his right hand, but has an assortment of knived and clawed substitutes with which to be nefarious.

Gaining access via Han’s annual martial arts tournament, Lee is joined by Roper (John Saxon), needing the prize money to pay off loan sharks, and Williams (the late, great Jim Kelly) an African-American on the run after assaulting racist cops.

However, with the tournament rigged against the interlopers, which of them will survive?

Enter the Dragon was to make history as the first American and Chinese co-production, with funding also coming from Golden Harvest and Lee’s Concord Productions. Shooting would take place on location in Hong Kong and at Golden Harvest’s studios.

But what makes Enter the Dragon so special is its place in Hong Kong action cinema.

Robert Clouse is officially the director, but Lee and his fellow Chinese actors and crew were not simply for hire; they are a who’s-who of Hong Kong action cinema.

The stocky student Lee fights at the beginning is legendary actor and fight choreographer Sammo Hung. Hung was a child graduate of the Peking Opera School and performed in a troupe called The Seven Little Fortunes.

Other Fortune members appearing in Enter the Dragon include Lee’s stunt double Yuen Wah, plus Jackie Chan, the only Hong Kong star other than Bruce Lee to become a global household name.

Other Fortune members appearing in Enter the Dragon include Lee’s stunt double Yuen Wah, plus Jackie Chan, the only Hong Kong star other than Bruce Lee to become a global household name.

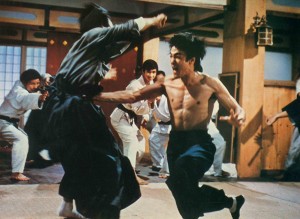

Chan is a student watching the opening fight with Hung, and later crops up as one of the dozens of guards Lee battles, succumbing to a vicious neck break (right).

10-time body-building champion Bolo Yeung is Han’s henchman Bolo, who famously crushes a minion to death at Han’s behest.

Lee’s sister is played by Angela Mao, the Michelle Yeoh of her day. Mao is permitted some butt-kicking before her demise at the hands of Bob Wall’s evil henchman Oharra, thereby making Lee’s mission personal as well as professional.

And the villainous Han is portrayed by Shih Kien (below), a grand old man of Hong Kong cinema. A figure of Christopher Lee stature in the Hong Kong film industry, his casting was a canny attempt for the local market to blend a stalwart of HK cinema with its current bright star.

What the film didn’t have for three of its ten week shoot was Bruce Lee. Weintraub recounts how Lee was too nervous to show up on set, and “On the first day, he had this facial twitch. We needed twenty-seven takes. The he settled down and we made the film.”

What the film didn’t have for three of its ten week shoot was Bruce Lee. Weintraub recounts how Lee was too nervous to show up on set, and “On the first day, he had this facial twitch. We needed twenty-seven takes. The he settled down and we made the film.”

Lee’s nerves are not surprising. He was getting the chance to prove what he had been saying all along, that he was the best martial artist on the scene. What if all his philosophy and training failed him at the crucial moment?

He need not have worried. Surrounded by martial arts masters including karate champions Wall and Kelly, and a proficient martial artist in Saxon proved Lee was not merely good because everyone else was bad.

Lee was the real deal and the movie knowingly used a technique first employed in The Big Boss: tease the audience with hints of what the star is capable of before unleashing fury.

Bar the opening sparring scene with Sammo Hung, Lee does little fighting for almost an hour of 105 minute running time. But, his natural charisma and trademark glare deliver a wallop almost on par with the nunchucks he later flails.

Bar the opening sparring scene with Sammo Hung, Lee does little fighting for almost an hour of 105 minute running time. But, his natural charisma and trademark glare deliver a wallop almost on par with the nunchucks he later flails.

While Lee prepares for the climactic showdowns, Saxon and Kelly (left) provide tasters through their bouts. Kelly gets one of the film’s best scenes when he battles Han himself in a psychedelic opium den, a sequence as weird as it is memorable.

But, what audiences most remember about Enter the Dragon is the final third, when Lee lets loose martial arts mayhem. For years UK audiences could only see a watered down version of this spectacular action, the BBFC making trims to “imitable techniques” and exorcising completely the nunchucks, even when they are slung around Lee’s neck! The 1980s UK video sleeve bore the dread phrase “BBFC Edited Version”, a disappointing notice to fans they were missing precious footage of their hero in action.

The movie was finally passed uncut in July 2001, almost thirty years after its release. Audiences could now see Lee at his physical best, the amazing fight scene with Han’s guards in his underground base a masterclass in Lee’s screen style.

Beginning in slow motion, presumably so audiences at the time could become used to the speed of the action (it really is “fast as lightning”), it showcases Lee’s philosophy of free-flowing fighting styles. Beginning with fists and feet and his patented squawks and grimaces, Lee graduates to staff, fighting sticks and finally nunchucks in a scene paid homage in Oldboy’s celebrated hammer fight set-piece.

Audiences seeing Lee for the first time were witness to a new breed of action hero and a performance style so theatrical it almost resembled the depiction of a traditional villain. Or as film professor David Bordwell puts it:

“(There are moments) after Lee delivers a punch his brows knit, his head swivels, and his mouth opens in astonishment at the damage he has done or draws into a grimace mixing strain, anger, and anguish.” – Bordwell, Planet Hong Kong

Not bad for a man with myopically bad eyesight and one leg shorter than the other. No wonder heir apparent Jackie Chan went the comedy route rather than challenge the master.

While Enter the Dragon drew inspiration from popular genres of the day, it looked back to film noir for its unforgettable climax. Riffing on Orson Welles’ The Lady from Shanghai, Lee’s confrontation with Han occurs in a vast hall of mirrors (reportedly 8,000), is a virtuoso set-piece of movement, choreography, illusion and technical bravado (you’ll look in vain for a stray reflection of a soundman or camera operator).

Enter the Dragon was a B-movie, but like its star punched well above its weight and landed 13th position in 1973’s US box office champs (No.1 was The Exorcist, another Warner Bros picture offering audiences something they’d never seen before).

It remains rough around the edges, scented with a vague whiff of fromage and the breathless plot doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

But, it is one of cinema’s finest action movies and it is fascinating to think how Lee would have built on its themes and philosophies in later movies. He was planning this on his next film, Game of Death, only partially completed before his death.

As there was no-one at the time to match him in dexterity and charisma, Western kung-fu cinema slunk back to the grindhouse ghetto in the 1970s taking Jim Kelly with it, and was a staple straight-to-video genre in the 80s, where Jean-Claude Van Damme and Cynthia Rothrock became living room stars (Rothrock’s China O’Brien being produced by Weintraub and directed by Clouse).

Hollywood took almost thirty years to catch kung-fu fever again with The Matrix (another Warner Bros picture that dazzled audiences with sights they’d never seen before). Had Lee lived he would have been in his late 50s when that movie was in production. It is hard to imagine the Wachowski’s would not have come calling.

Hollywood took almost thirty years to catch kung-fu fever again with The Matrix (another Warner Bros picture that dazzled audiences with sights they’d never seen before). Had Lee lived he would have been in his late 50s when that movie was in production. It is hard to imagine the Wachowski’s would not have come calling.

But his spirit lives on in The Matrix’s on-the-sleeve philosophy. Or in the great man’s own words:

“Don’t get set into one form, adapt it and build your own, and let it grow. Be like water. Water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

Long live the Dragon.

Rob Daniel

Sources:

Enter the Dragon, dir. Robert Clouse (Warner Home Video, 2007 Blu-ray edition)

Planet Hong Kong, David Bordwell (Harvard University Press, 2000)

Hong Kong Action Cinema, Bey Logan (Titan Books, 1995)

From Bruce Lee to the Ninjas – Martial Arts Movies, Richard Meyers, Amy Harlib, Bill & Karen Palmer (Citadel Press, 1985)

Pingback: Lee-mendous! The Top 10 Greatest Bruce Lee Moments - Electric Shadows