#3 – M (1931)

Director: Fritz Lang

Cast: Peter Lorre, Otto Wernicke, Theodor Loos, Ellen Widmann

Cert: PG

Running time: 110mins

Year: 1931

Accolades:

National Board of Review (1933)

Top Foreign Film

Contemporary review:

“(like) looking through the eye-piece of a microscope, through which the tangled mind is exposed…” – Graham Greene

Electric Shadows rating: ![]()

The lowdown: A still relevant, still troubling, still influential masterpiece, Fritz Lang’s M only improves with age. Peter Lorre was forever typecast as the sensitively portrayed child murderer who becomes the target of Berlin’s police force, criminal underworld and the increasingly vengeful mob. Lang’s pessimistic view of contemporary German was jaundiced by the rising popularity of the Nazi party, and the portrayal of a population manipulated into murderousness was all too prescient. Technically dazzling and morally complex in the best sense of the word, this remains required viewing.

The full verdict: Even to eyes weary of countless police procedurals and increasingly graphic serial killers on screens large and small, M still hits hard.

Fritz Lang, hungry for a hit after two failures with Metropolis and Woman in the Moon, tore the story for his next movie from the newspapers of the day. And serial killers clearly held the same fascination back then as they do now.

Although not directly based on the life of any murderer, Lang acknowledges M was influenced by the crimes of Fritz Haarmann, Carl Grossman, Karl Denke and Peter Kurten (the Vampire of Dusseldorf), who terrorised different regions of Germany during the 1920s.

The masterstroke of M is that the story, written by Lang and his then-wife Thea von Harbou, keeps Lorre offscreen for the majority of the movie, focusing instead on the social impact of his acts.

A police procedural long before the term was coined, M is a forensics movie, with scenes of pathologists and graphologists examining what scant clues exist (including a From Hell style letter to a newspaper) that must have fascinated contemporary audiences and was echoed in Michael Mann’s Manhunter.

With arch black comedy, Lang intercuts the police investigation with the underworld’s own hunt for the killer, the two groups looking more alike as they pore over maps of Berlin in dingy smoke filled rooms.

Although Lang’s first talkie the director exploits the new technology to maximum effect, marrying it to his visuals with a Wellesian glee at the possibilities on offer.

Long before Reservoir Dog’s Stuck in the Middle With You or A Clockwork Orange’s Singin’ in the Rain, M may be the first movie to transform a piece of existing music through the context of the film. Lorre’s Hans Beckert repeatedly whistles Grieg’s In the Hall of the Mountain King, and that slow-build, nursery rhyme like composition is employed to great effect for tension, but also as a window into Beckert’s mind, the killer whistling the tune to calm himself after a young girl unknowingly escapes his clutches.

Lang also uses unnerving silence, draining dramatic moments of all sound only for the quiet to be broken by the murderer’s whistling (actually director Lang), a shrill police whistle or a layering of one voice on top of another, building to a hysterical cacophony as crowds gathers around a newspaper vendour with news of the latest atrocity.

And suitably for a social horror movie, the director fills his film with different accents to depict how the acts of one pathetic individual cuts across the social strata (and to a 1930s audience Lorre’s Austrian accent would have marked Beckert as an outsider).

French and English versions of M were also prepared, replacing actors and reshooting scenes. The excellent Masters of Cinema release contains the rediscovered, damaged English language version. Interesting for Lorre’s first English language appearance, but as Lang was not involved in the preparation it pales beside the original cut.

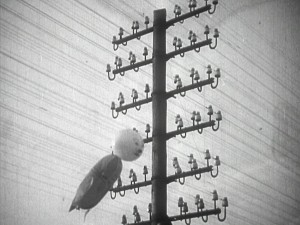

But, the man who directed Metropolis is not going to forsake the visual and M is filled with noir-ish masterstrokes. A girl bouncing a ball on the “Wanted” poster upon which Beckert casts a shadow. That same ball discarded in a wasteland and the balloon with which Beckert lured the girl tangled in telegraph wires. A gang of children staring distrustfully at a barrel-organ operator. The chalk “M” on the killer’s shoulder, marking him for the mob. The first proper view of Beckert, aptly doubled in a mirror, the character staring at himself trying to find the monster within.

Beyond the formal brilliance, M is about people’s fears and prejudices and a bold acknowledgement that even society’s monsters deserve understanding, climaxing with a kangaroo court in which Beckert is tried by society’s criminals and outcasts.

What remains remarkable is how the dialogue of the accusers matches verbatim the tabloid hysteria of today’s media, how they’ll be pampered in mental homes and hanging is the only cure for their illness. But, Lang is too smart a filmmaker to tar the mob with one brush (no matter how much he distrusts it) and includes a haunting plea for justice for the victims and their families that is still shattering.

Most memorable in this scene is Peter Lorre’s performance, terrified and bug-eyed, brimming with self-loathing and anguish as he rants over hideous urges he can neither understand nor control. It may have typecast the actor much as Psycho would for Anthony Perkins (and Hitchcock must have been impressed with M, casting Lorre in 1934’s The Man Who Knew Too Much and 1936’s Secret Agent), but this is one of cinema’s greatest moments.

Like too many masterpieces, M has received brutal treatment through the years. Seven minutes were removed after its premiere – the missing scene depicting people confessing to the crimes, another aspect of the hysteria. While it would be useful to see this now lost scene, it would disrupt M’s central theme of what a unified mob is capable of when it turns on the outsider.

A little-liked, little seen American remake, also titled M, appeared in 1951.

Predictably, M itself was banned by the Nazis in 1933 and resurfaced in its homeland only in 1960, shortened to around 90 minutes. Various endings exist that replace the haunting final shot and dialogue (the reason Lang originally made the film) and dilute the film’s meaning.

Only in the late 1990s did restorations begin that would lead to the version now available, with Lang’s central message about man’s darker impulses intact.

Rob Daniel